1: 54 Contemporary African Art Fair London

“Art is a fluent matter so let’s go beyond localization of ideas, because thoughts are global. Besides, Africa is not blackness and blackness is also not Africa, but global. Let’s look at the different narratives that exist in history.”

A quote of Koyo Kouoh, curator of the Contemporary African Art Fair 1: 54 in London.

1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair goes beyond ‘Black Africa’

From 15th-18th October the third London edition of the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair was held in Somerset House, London. The name 1:54 refers to the fifty-four countries which make up the African continent and the diversity and multiplicity of which the fair aims to exhibit. With 500 artworks by 150 artists from Africa and the African diaspora, 38 exhibitors and almost 15,000 visitors this fair is the biggest so far.

Conceptual boundaries

FORUM, the discussion programme that runs parallel to the fair, also discussed a larger geographical area than the previous editions. Through lectures, talks by artists, panel discussions, film screenings and book launches, FORUM integrated the Maghreb (the Arabic name for the NW part of Africa, generally including Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and sometimes Libya) and its intellectual and artistic relationship with so-called ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’ or ‘Black Africa’.

Koyo Kouoh

FORUM’S curator Koyo Kouoh explains: “Instead of seeing the desert as a cultural blockade or a conceptual socio-political boundary, it needs to be reconsidered as a transport route, especially in the light of the current refugees.” Kouoh points out that the time has come to stop the mutual exclusion of North and South Africa and realise that the Maghreb also belongs to the African continent and Egypt is not ‘an archaeological island off the coast of American universities.’ It’s time to readdress the construction of these geographical cultural divisions. Kouoh emphasizes: “In a world of migration and globalization, themes such as provenance, history and the politics of identity form the core of the discussions and critical reflections held in this edition of FORUM.”

The writer in the audience

Multiple Identities

As a result of the fair’s theme more galleries from the Maghreb attended and hence more artists from this region and its diaspora exhibited their work than previously. This was immediately apparent in the 1:54 fair’s lounge which was designed by Hassan Hajjaj, an artist from the Maghreb. The design combines multiple African identities such as typical Sub-Saharan wax prints, Coca Cola crates with Arabic lettering but also North African street iconography covering photography, painting, furniture design, album covers, and restaurant interiors as well as references to European pop culture. It leads back to Hajjaj’s own dual cultural experiences, having lived in Larache, Morocco and in London.

From the Rock Star Series, Hassan Hajjaj

From the Rock Star Series, Hassan Hajjaj

Nidhal Chamekh: Reconsidering history

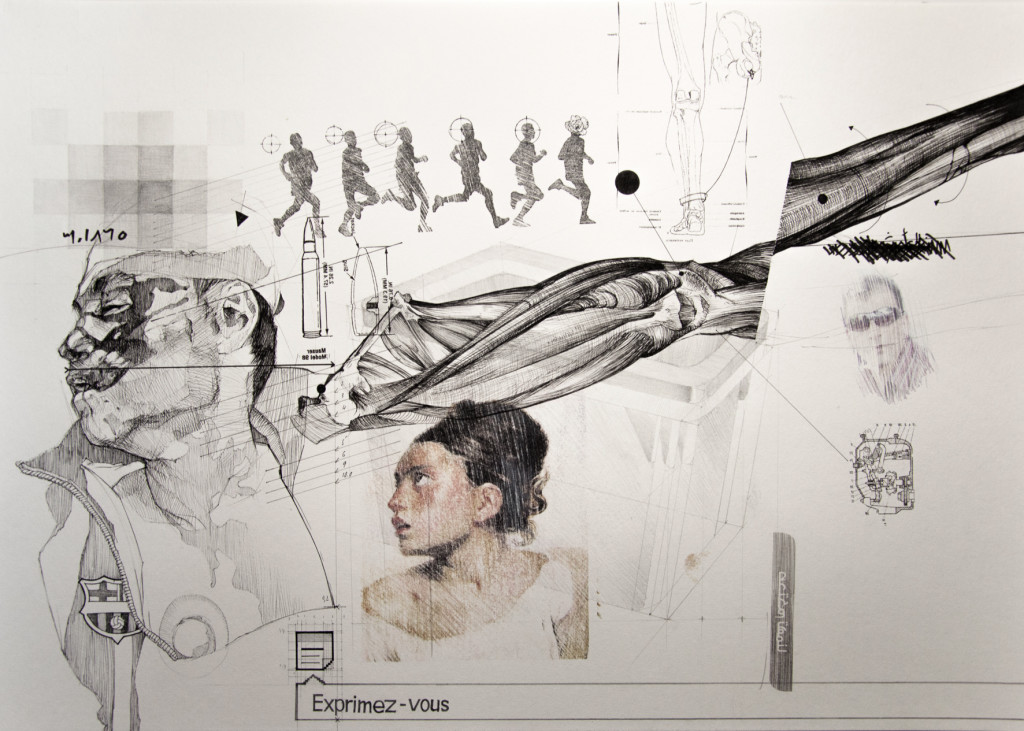

Another visual artist from the Maghreb is Nidhal Chamekh who divides his time between Tunisia and France. His current work consists of graphite and pencil drawings in which he explores political and historical events, such as the popular uprising during the Arab spring in Tunis.

Nidhal Chamekh, Dessin nr. 6, 2012.

An example is Chamekh’s series entitled ‘What do Martyrs Dream of?’ The series contain figures with highly emotional expressions inspired by Tunisia’s contemporary politics. He assembles these figures with heterogeneous elements of popular European culture that have no apparent relation to politics. It shows the anecdotal correspondence between images that create a different way of looking at political contexts. Chamekh explains: “I find it hyper-interesting to consider history as a connection between events and not as something completely linear.” His drawings are meeting points of elements from different places, times and periods.

Nidal Chamekh, Dessin nr. 6, 2012.

Nidal Chamekh, Dessin nr. 6, 2012.

Chamekh’s latest work consists of a series of diptychs, entitled ‘Extractions’ in which he also creates bridges between the past and present. He comments on the power of colonialism by drawing detailed pictures of the machinery used by Europeans to denude the African landscape of its raw materials. The themes of these drawings are movement and travel combined with nature and landscape. Chamekh states: “These virgin landscapes were not exploited for industrial or any other purpose and were then confronted with instruments which almost destroyed them during the process of extraction. They show the domination by man.” Chamekh uses images of the machinery from old European encyclopaedias in which they were presented as inventions and instruments of progress.

Chamekh concludes: “In the construction of modern states in Africa, economies are still largely based on extraction as opposed to transformation. The destruction is still going on.”

Joana Taya, Endangered Beauty, 2015.

Joana Taya, Endangered Beauty, 2015.

Joana Taya: Homage to tribal cultures

History and provenance are themes that also suit Angolan visual artist and graphic designer Joana Taya. Born of an Angolan mother and a Portuguese father she is currently living and working in Norway. This creates a desire in her to explore her Angolan roots and female identity. Taya states: “Every time I go north, I go south in my heart.” In her work she draws attention to the social position of women in Angolan society and to ordinary citizens in the street.

Taya gives an impassioned plea for a more humane approach to development in Africa in her series ‘Endangered Beauty’: “It’s about humanity; we are developing the world, but what about people and nature? This series is a homage to tribal cultures where people used to live in peace and harmony with each other and their environment. Nowadays people only seem to be preoccupied with the economy, which in Angola stands for oil, diamonds and coffee. People are selfish! Think about Angolans who had to fight in the war and now they have no legs and are abandoned in the streets, nobody cares about them!”

Joana Taya works Endangered Beauty, skateboard, 2015

Taya wants to create awareness about the beauty of tribal cultures in general and of Angolan tribes in particular. She does this by using their colours, symbols and traditions in a contemporary context. In one of her works she depicted an Angolan woman from the Mumuila tribe. The woman is wearing beads around her chest and rings around her arms and legs and lying on richly patterned traditional fabrics. In contrast she is holding a skateboard symbolising her contemporary context.

Taya explains: “I could be that woman, I am very modern but I am still a proud Mumuila in my heart. This tribal woman is accepted for who she is and where she comes from but lives in contemporary society as a modern woman.” Knowing one’s identity creates confident people, no matter where they physically are, according to Joana Taya.

Ernest Dükü: Memory of the Past

In the same way that Taya explores tribal cultures to understand and appreciate her identity, Ivorian painter and sculptor Ernest Dükü also questions the relationships between history and the politics of identity. He explores the heritage of colonialism and how it relates to postcolonial socio-cultural conditions in Africa and its diaspora. His current work consists of collages of pencil, watercolour and texts from magazines on creased paper.

Dükü is interested in religion and how it’s perceived in Africa in colonial and postcolonial times. He observes a transformation of how Africans consider their faith. It changed from animism with a thin coating of Christianity or Islam in colonial times, to undiluted Islam or Christianity in postcolonial times. According to Dükü this change is a reflection of how the west looked down on animism, an attitude that was absorbed by the Africans themselves, although the result is paradoxical.

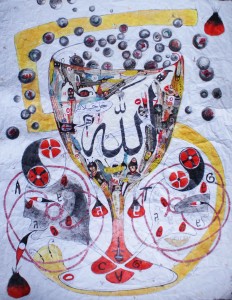

Ernest Dükü, Intemporel 5 @ connexion amulettissimo, 2015

He explains: “The way people experience religion, goes back to their history and culture. Our personal history determines our view of the world. It creates our frame of reference through which we perceive the world. I want to confront the viewers with this reality. Contemporary Africans mostly despise animism, but are actually still animists, because they continue to consult a marabout – animistic sage or saint- if they have problems. I don’t want to judge, because there is no right or wrong. I just want to create awareness about the politics of identity which are based on one’s memory of the past. In the end we are all people formed by a mix of cultures and its values and symbols. You have to accept that it is a blend.”

Ernest Dükü, Seinblyquement votre, 2015.

Ernest Dükü, Seinblyquement votre, 2015.

Via a diversity of symbols, he examines the contrast between the untouched people we are when we are born – the so-called DNA codes – and the people we become while growing up in cultures and environments that shape us. He uses syncretism, or the combination of the symbols of different religions, combined with DNA-codes. Dükü depicts for example an animistic sculpture that rises from a Christian chalice and is surrounded by symbols of other religions. He explains: “Everything in the human world has consisted of symbols as long as mankind has existed. Yet it is said that Africa has no history, because it is not written down in text. But there is an African history that is recorded by means of symbols. That’s why I use numbers and symbols; it is a criticism of this attitude and a desire to show how the symbolic can revert to its former glory.”

Ernest Dükü

African Art: A label?

The term ‘African Art’ is not a label, but a context according to Ernest Dükü. He states: “It’s obvious that no form of expression can be manifested without identity, without culture and geographical location. If I wasn’t born and raised in Ivory Coast than I probably would not address the themes that I do now. On the other hand, geographical location should not be necessary to mention, because it is evident that every artist draws from his own context, wherever that may be. Art is what my memory allows me to communicate and it’s a result of my background.”

The location: Somerset House, London.

When it comes to emphasising the geographical locations of artists, Ernest Dükü shares the view of 1:54 FORUM curator Koyo Kouoh. She states: “Art is a fluent matter so let’s go beyond localization of ideas, because thoughts are global. Besides, Africa is not blackness and blackness is also not Africa, but global. Let’s look at the different narratives that exist in history.” In a sense, new narratives of history were written during the four-day 1:54 African Art Fair. On the one hand the focus is now truly on including all 54 nations of the African continent and on the other, origin and identity are now being considered in a global context in which there is a sense of the nomadic in all artists.