Thierry Oussou

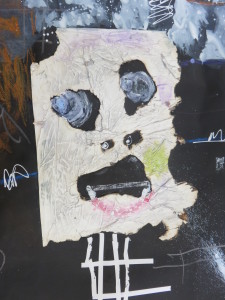

“Suffering feels like coals that burn on your skin. That’s what I do with paper. I paste multiple layers of different types of paper onto each other and then I burn holes in it with coals.” Oussou stresses: “Remember, without suffering there is no happiness.”

Rosalie van Deursen on the work of Thierry Oussou, one of the artists in ‘What about Africa?’ at Witteveen Visual Art Centre, Amsterdam.

Trace XI, 2015.

Thierry Oussou

No Happiness without Suffering

“Paper is an important material. We can’t live without paper, it’s like clothing. You can’t go to school or travel, your birth certificate is written on paper when you are born and then your history starts. Your history is created through all those pieces of paper.” Oussou sees a link between this accumulation of paper throughout our lives and the inevitability, that rich or poor, we will all encounter some suffering. He explains: “Suffering feels like coals that burn on your skin. That’s what I do with paper. I paste multiple layers of different types of paper onto each other and then I burn holes in it with coals.” Oussou stresses: “Remember, without suffering there is no happiness.”

Detail from series Trace , Collage, Acrylic Ink Color Pencil on Paper, 2015

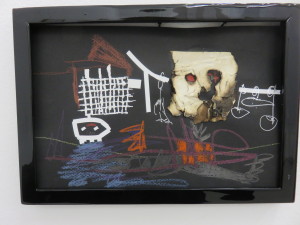

My Potato Field

Thierry Oussou, who comes from Benin and is currently artist-in-residence at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, works with heavy paper or newspapers and acrylic paint and glues layers of paper on top of each other to form a relief. “In newspapers you’ll find the history of a particular day. History is made up of layers as humans are too.” During the Open Days at the Rijksakademie, he exhibits a wall with 61 small drawings in brightly colored frames. Each work consists of black paper with a drawing in bright colors and a human figure with a burnt mask. The work is entitled ‘My Potato Field’. He explains: “Potatoes are important because they are part of our staple diet and so they function as a symbol of personal aspects in our lives. Actually, it’s not MY potato field, but that of the viewer, because the viewer is the one who might recognize himself.”

My Potato Field, installation, 61 slates, 2015.

Behind the mask

Daily life is Oussou’s main source of inspiration. Newspapers and stories of friends’ experiences fascinate him. He works with different media, such as videos and installations, but mostly with paper. ‘My Potato Field’ represents many facets of everyday life. There is a lot to see, a human figure with a windmill, a purple car, a Black Pete, white flags, guns and tanks, but also sheep, goats and a woman on a beach. By using masks and universal themes Oussou aims to be accessible to a diverse audience. He explains: “Everyone can hide behind a mask. I don’t know your past or present, but perhaps there is something in my pictures that you recognize in yourself. Each mask is a person, an individual composed of several layers. Maybe you can identify with some part of my drawings.”

My Potato Field, detail, 2015.

My Potato Field, detail, 2015.

The world as a fabric

The 61 frames represent the colors of various national flags portrayed in unconventional combinations. Oussou explains: “I can also present the colors in order to associate more clearly with a flag of a particular country. But this time I’ve decided to mix all the colors. In this way I hide possible political associations.” Oussou chooses to make his messages more abstract to avoid provocation. His everyday subjects often explore essential questions reflecting the struggle between the individual and society and between humankind and power or nature. He explains how his work reflects politics: “Potato fields are universal. Someone can have his field next to another person but at the same time they are separated from each other by a border. It is invisible to the eye but there are two territories based on politics.”

He elaborates on the alienating effect of political decisions he faced in Congo. “A river separates Congo Brazzaville from Congo Kinshasa and you even need a visa to cross the river!” This phenomenon is unnatural to him; he sees the world more like a piece of fabric that is naturally woven together.

Hunger for knowledge

Thierry Oussou looks back at his past: “An enormous desire for knowledge and curiosity has made me who I am. I have been drawing since I was seven and even though I was a shy boy, I knew exactly what I wanted, to be someone who communicates via art. And because there are no art schools in Benin, I taught myself everything. I am a self-taught.”Oussou visited exhibitions, helped artists in their studios or during exhibitions and workshops. He read widely about artists, techniques, and materials. He also travelled extensively throughout West Africa to meet and learn from other artists. Oussou stresses that it has not been easy: “My parents were strongly opposed. They wanted me to become a police officer or a lawyer. Only when I won an award for a video and travelled to Egypt for the exhibition were they proud of me.”

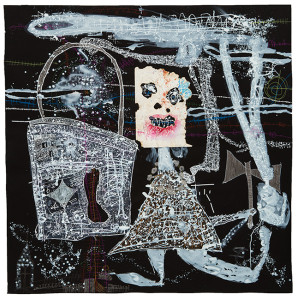

Trace X, collage, acrylic, ink, color pencil on paper, 152 x 152 cm, 2015.

Leaving traces

In Oussou’s previous series ‘The Traces’ large sheets of black paper contrast with white and colored drawings that are always accompanied by a figure with a burnt mask. One of the works from this series shows a lion, a chair and two debating human figures. One figure is a leader who rules over anonymity, depicted by a mask. It is Oussou’s reflection on the course of events surrounding the elections in Benin.

Trace VII, collage, acrylic, ink, color pencil on paper, 152 x 152 cm, 2015.

Another important theme in ‘The Traces’ series is caring for the environment. As he says: “It’s like gold, we must protect it!” He juxtaposes the development of modern society against elements that often represent Beninese heritage. Oussou explains: “In Benin a turtle symbolizes wisdom; he is slow but thoughtful and knows the road better than anyone else! Also, a turtle protect itself from the outside world and lives in harmony with its surroundings.” Oussou hopes to encourage his viewers to contemplate the traces they leave behind, whether it’s in nature, politics or otherwise.

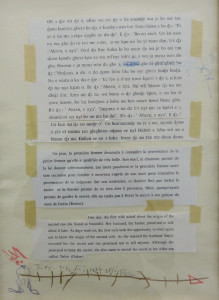

A Common House, installation, 2015.

Transformation into an animal

To draw attention to his work, Oussou presents his artworks in a particular manner. In the installation ‘A Common House’ (2015), which he exhibited during the Open Days at the Amsterdam Rijksakademie, frames were hung from the ceiling. He framed texts in Fon, a Benin language, English and French and illustrated the texts with little drawings. The work is a reference to a 13th century Beninese story. Oussou explains: “I have deliberately presented it like this, to make people curious.” He wants to make this oral history as told by a traditional storyteller in Fon accessible by translating it into English and French. “The story took place in the 13th century in Allada, in the south of Benin, but now the same things happen everywhere in the world. It’s about love, war, migration and the lust for power. In the 13th century story an animal transforms itself into a woman, but I would say that nowadays it is humans who are transforming themselves into animals. They make weapons and go to war to kill each other.” Oussou wants to highlight the universality and contemporaneity of this oral history.

A Common House, installation, detail, 2015.

Focus on knowledge

Oussou is and remains very eager to learn, so he is very pleased with his artist-in-residency in Amsterdam. Oussou emphasizes: “I learn so much from other international students and from living in a different culture. My mind is expanding and the world is far bigger than the culture I know and my own little ideas. Art is a universal matter, without limits.” He points out that artists play an important role in society: “I’m free to express what I observe, because I’m not affiliated with any organization. Hopefully my work makes people think and consider things differently.”

Thierry Oussou not only intends to continue developing himself, but also finds it very important that children learn about art. In Benin, he created art clubs at several schools and organized children’s workshops in Brussels and Copenhagen. In addition he launched an artist-in-residence in Benin where young artists can meet and exchange ideas. He explains passionately: “Sharing knowledge is important, it has made me who I am. Many people in my life shared their knowledge with me without expecting anything in return. Oussou’s message to children is to be creative and live their dreams and to remember to respect and love paper; the material we can’t do without.”